A couple of years ago when completing a condensed MBA course, I noted to one of the course advisors that the section on policy would benefit from having more emphasis on mainstream economic theory, rather than focusing exclusively on behavioral economics. In response, the course advisor suggested: “You should read ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ by Daniel Kahneman.”

I decided to hold my tongue: both because I couldn’t think of a nice way to respond to someone brushing away centuries of economic theory so casually and as I was a little embarrassed to admit that I still hadn’t read the book, despite it being released a decade ago. This isn’t to say that I hadn’t been interested or engaged in the field, only that I had neglected to read one of the key books that popularized it.

Reading Fast and Slow, Slowly…

So in 2021, a decade after the book was released, I finally read it. Fully aware that the book had been released just before the replication crisis hit psychology.

But, I wasn’t reading the book out of spite. I’m an active advocate for many of the standards applied by behavioral economics, such as the field’s willingness to question everything and conduct trials of interventions, rather than just assuming an intervention will work.

But, does it blend replicate?

38 chapters later Kahneman can return from the edge of his seat: it’s a great book. Entertaining, insightful and a breeze to read.

But, knowing the challenges faced by the field after it was released, I had to ask “Are the book’s findings valid?”

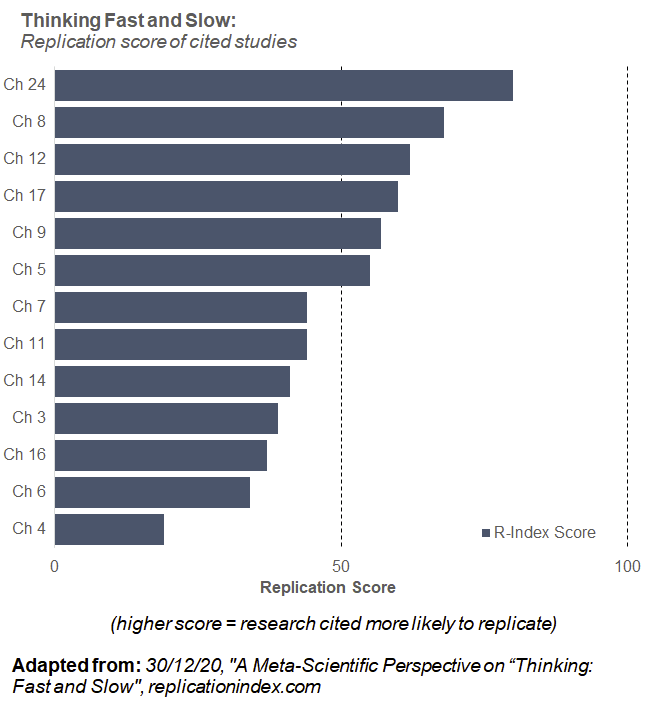

Leading me to this interesting analysis from Ulrich Schimmack, Moritz Heene, and Kamini Kesavan of replicationindex.com. In the piece, the researchers calculate an ‘R-Index’ score for the likely replicability of the research cited in each chapter. You can read more about their analysis here, but in essence the higher the score, the higher the chance that results of the studies cited in the chapter will replicate if repeated (or the lower the chance results cited in a chapter were a statistical fluke).

I’ve summarized their calculated R-index scores in the plot below. A score below 50 implying that there is a less than 50% chance that a result will be replicated if the research was repeated again. In essence, a score below 50% implies that on average the evidence used for a chapter aren’t likely to be reliable:

Overall, of the 13 chapters that cited empirical results, 6 of them have an R-score above 50. Meaning that most of the chapters rely on research that has low statistical power, leading the authors of the research to conclude:

“…Readers of “Thinking: Fast and Slow” should read the book as a subjective account by an eminent psychologists, rather than an objective summary of scientific evidence. Moreover, ten years have passed and if Kahneman wrote a second edition, it would be very different from the first one.…”

Ulrich Schimmack, Moritz Heene, and Kamini Kesavan, “A Meta-Scientific Perspective on “Thinking: Fast and Slow”

But, what about those chapters that received a passing grade? Surely there are insights from the book that the course advisor can continue to latch onto?

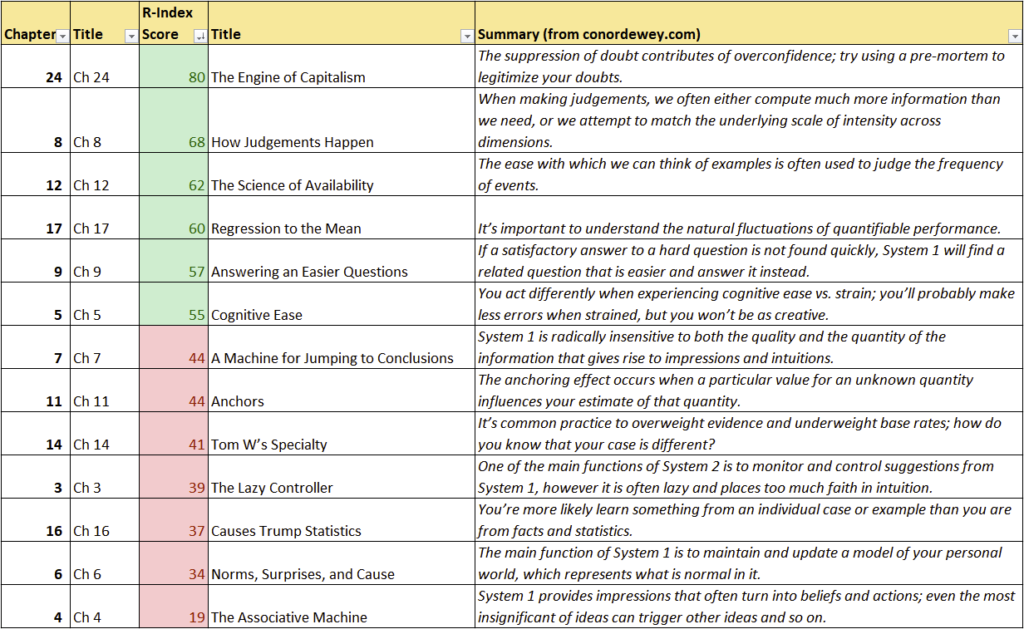

Well, noting that this is a less than perfect approach for answering this, I’ve created a table of each chapter, its R-Index score and a short summary of what the chapter covers (from conordewey.com):

Note: the chapter summaries have been taken from Conor Dewey (2/3/23), “Every Chapter of Thinking Fast, and Slow in 7 Minutes” link here

Again, there are a lot of assumptions needed to interpret the implications of the R-Index scores in this way. But, I’ve found it to be a helpful way to focus on the ideas I need to re-evaluate.

The essence of the results is essentially this: many of the book’s claims about how system 1 works (and doesn’t) warrant revisiting.

I should also mention that Kahneman responded to the Schimmack et. al’s research, noting:

“…Clearly, the experimental evidence for the ideas I presented in that chapter was significantly weaker than I believed when I wrote it. This was simply an error: I knew all I needed to know to moderate my enthusiasm for the surprising and elegant findings that I cited, but I did not think it through….

So, Thinking Fast and Slow is perhaps not a reliable theoretical cornerstone for public policy. But hats off to Kahneman for not hiding from the problem. That’s how science should work after all.

Leave a Reply